By Anthony J. Scillia MD

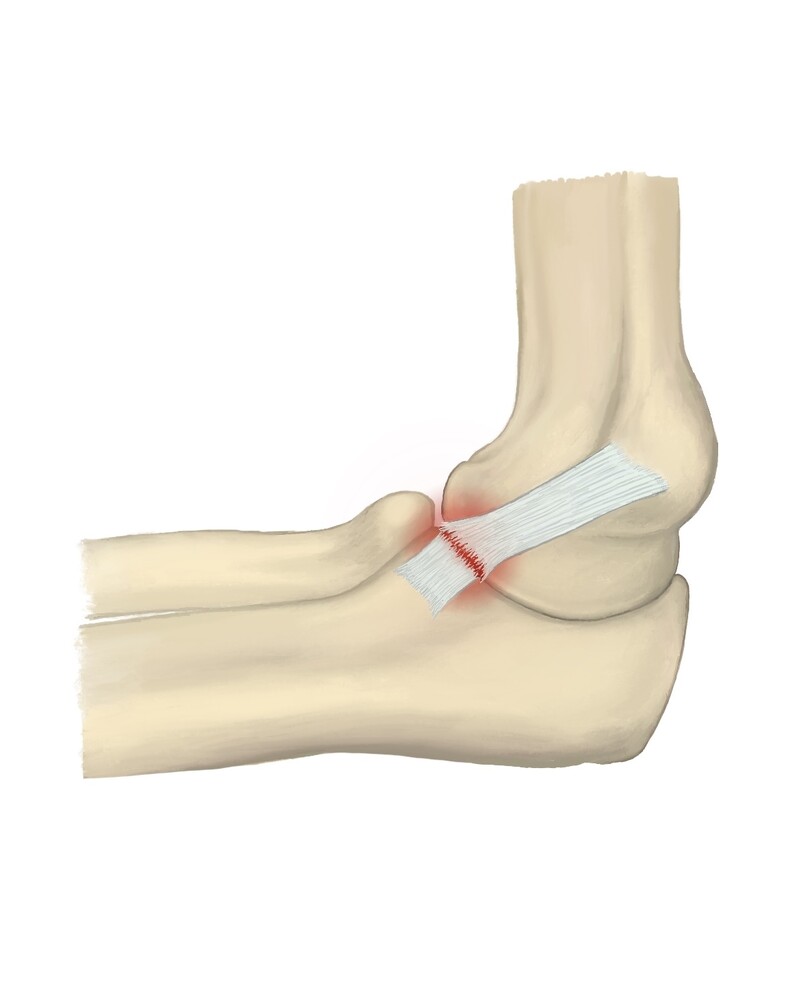

Dr. Frank Jobe famously repaired the medial ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Tommy John in 1974. Since then, over 1000 professional pitchers – along with many other athletes like gymnasts, wrestlers and javelin throwers – have had Tommy John surgery. Through the efforts of great surgeons like Dr. Jim Andrews, Dr. Jeff Dugas and Dr. Lyle Cain of the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham, where I did my fellowship, the surgery itself has evolved and improved, decreasing rehabilitation time from 18-24 months to six to nine months.

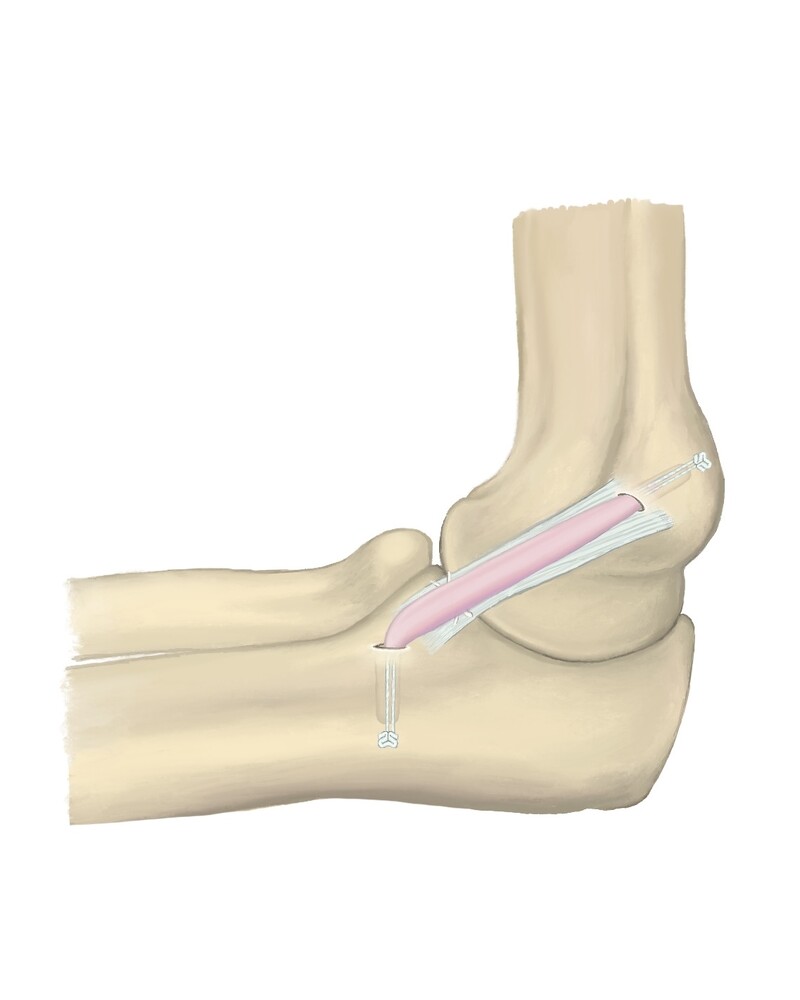

Dr. Andrews’ modified Jobe procedure has proven durable success in returning athletes of all levels to play. However, it takes more than one year for the graft to incorporate itself into the body and be able to withstand the high levels of stress necessary for throwing. Dr. Dugas designed the “Tommy John Light” procedure to decrease that return-to-sport timing to six months by repairing the native ligament and using an Internal Brace to stabilize the elbow time zero. Over my 12 years in practice, I have developed a hybrid technique for Tommy John surgery that draws on both procedures by combining the excellent long-term results of Dr. Andrews’ graft reconstruction with the early return-to-play of Dr. Dugas’ Internal Brace technique.

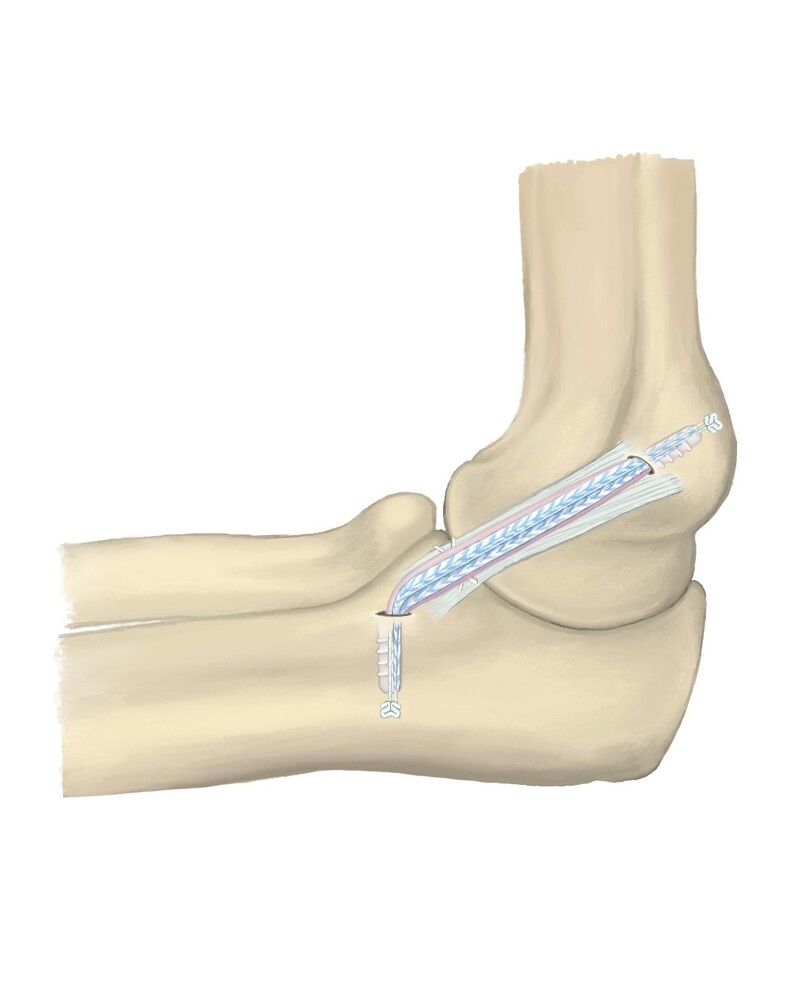

The procedure, known informally as “Hybrid Tommy John Surgery,” is a muscle-splitting ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with an allograft and internal brace. Essentially, I do a procedure with a smaller incision, fewer drill holes in the bone and added collagen and support to provide immediate stability and allow for early rehabilitation. It has both the faster return to play seen in Tommy John Light surgery and the long-term durability of a reconstruction.

The Incision/Accessing the UCL

The incision Dr. Jobe made along the inside of Tommy John’s elbow was nearly four inches long because he detached the flexor-pronator mass – the large group of muscles on the inside of the elbow – to access the UCL and to allow full access to the epicondyle of the humerus and the ulnar nerve. Dr. Andrews later developed a muscle elevation technique to avoid detachment of the flexor-pronator mass, minimizing damage to the muscles. In my hybrid technique, I use this approach or a muscle-splitting approach to avoid the ulnar nerve if there is no ulnar nerve irritation, allowing for a much smaller, 1.5-inch incision.

The Graft

In 1974, Dr. Jobe harvested the palmaris longus tendon from John’s left wrist and used it in his UCL repair. However, less than 20% of the population has a palmaris longus tendon and it is typically quite small and thin. The alternative has long been the gracilis tendon at the back of the knee, which is stronger and more collagen-dense than the palmaris. However, using a gracilis autograft can result in knee pain or weakness and can be problematic for pitchers whether taken from the landing or drive leg. Instead, I use an allograft – most often a gracilis tendon harvested from a cadaver – in my hybrid UCL repair. If the gracilis is too large to fit in the elbow of a smaller athlete, it can easily be trimmed down to size.

Bone Work

Dr. Jobe’s original procedure involved drilling two large holes in the ulna, the lower arm bone, and two in the humerus, the upper arm bone. In Dr. Andrew’s modified Jobe procedure, five slightly smaller holes are drilled – two in the ulna and three in the humerus – through which the tendon graft is woven in a figure eight pattern and sewn to itself. However, the more drill holes in the bone, the higher the risk of post-surgical fracture. Due to advancements in suture anchor technology, I am able to drill just one tunnel in each bone – one on the sublime tubercle of the ulna and the other on the medial epicondyle of the humerus – which reduces the risk of post-surgical fracture by decreasing the size and number of drill holes. Drilling fewer holes in the bones is crucial, especially for pitchers who throw over 90 miles per hour whose bones must withstand a tremendous amount of torque.

The Internal Brace

Dr. Dugas pioneered the UCL internal brace, which utilizes FiberTape, made by the orthopedic medical device company Arthrex. FiberTape is a braided, ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, bovine-collagen-dipped version of a super suture that looks much like a shoelace. Inspired by Scottish orthopedic Dr. Gordon Mackay’s use of FiberTape in ankle surgeries, Dr. Dugas used FiberTape to strengthen UCL repairs by providing a framework against which the UCL can heal; imagine a tomato plant (the injured tissue) supported by a tomato stake (the FiberTape). However, Dr. Dugas primarily uses the Internal Brace to repair avulsions, or single-sided tears, in which the athlete’s own ligament is reattached to the bone. There is no graft. In my hybrid technique, I use the Internal Brace in combination with an allograft for both avulsions and mid-substance tears to increase the strength of the reconstruction. The beauty of the Internal Brace is that it’s stable at time zero, protecting the allograft as it heals and allowing athletes to immediately begin physical therapy to restore range of motion and strength.

Addressing Ulnar Neuritis

The “funny bone” is actually the ulnar nerve, which runs along the inside of the elbow and innervates the forearm, hand and ring and pinky fingers. Athletes with UCL damage often have accompanying ulnar nerve symptoms. Dr. Jobe’s procedure included a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition, during which the ulnar nerve is moved from the back of the elbow to the front, freeing it from impingement. Dr. Andrews switched to a subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition, in which the nerve rests just under the skin rather than beneath the muscle, leading to less compression of the nerve. In my hybrid technique, I use a muscle-splitting approach to avoid the ulnar nerve altogether unless the athlete has ulnar neuritis. In that case, I most often decompress it in its natural position by unroofing the cubital tunnel, giving it more room and minimizing potential trauma to the nerve.

Treatment for hip pain while walking depends on the underlying cause of the pain. While some pain may be managed with conservative treatments like rest and ice, others may require a surgical approach. The most common treatment methods for hip pain are:

Rehab and Return to Play

In 2010, Dr. Cain published a study looking at 942 patients who were operated on using Dr. Andrews’ Tommy John technique. 83% – 95% were able to return to their previous level of competition or higher in less than one year, with athletes still able to throw after retirement and very few retiring due to elbow issues. In my seven years of experience with my hybrid technique, I have had a 93% return-to-play rate with position players returning in four to six months and pitchers in six to nine months. I have had similar success with gymnasts, who have returned to competition in six months.